Inside Meta’s $725 Million Facebook Privacy Settlement: The Largest U.S. Class-Action Privacy Payout and What It Means for the Future of Data Governance

By Ramyar Daneshgar

Security Engineer | USC Viterbi School of Engineering

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

1. Introduction: A Turning Point for U.S. Privacy Enforcement

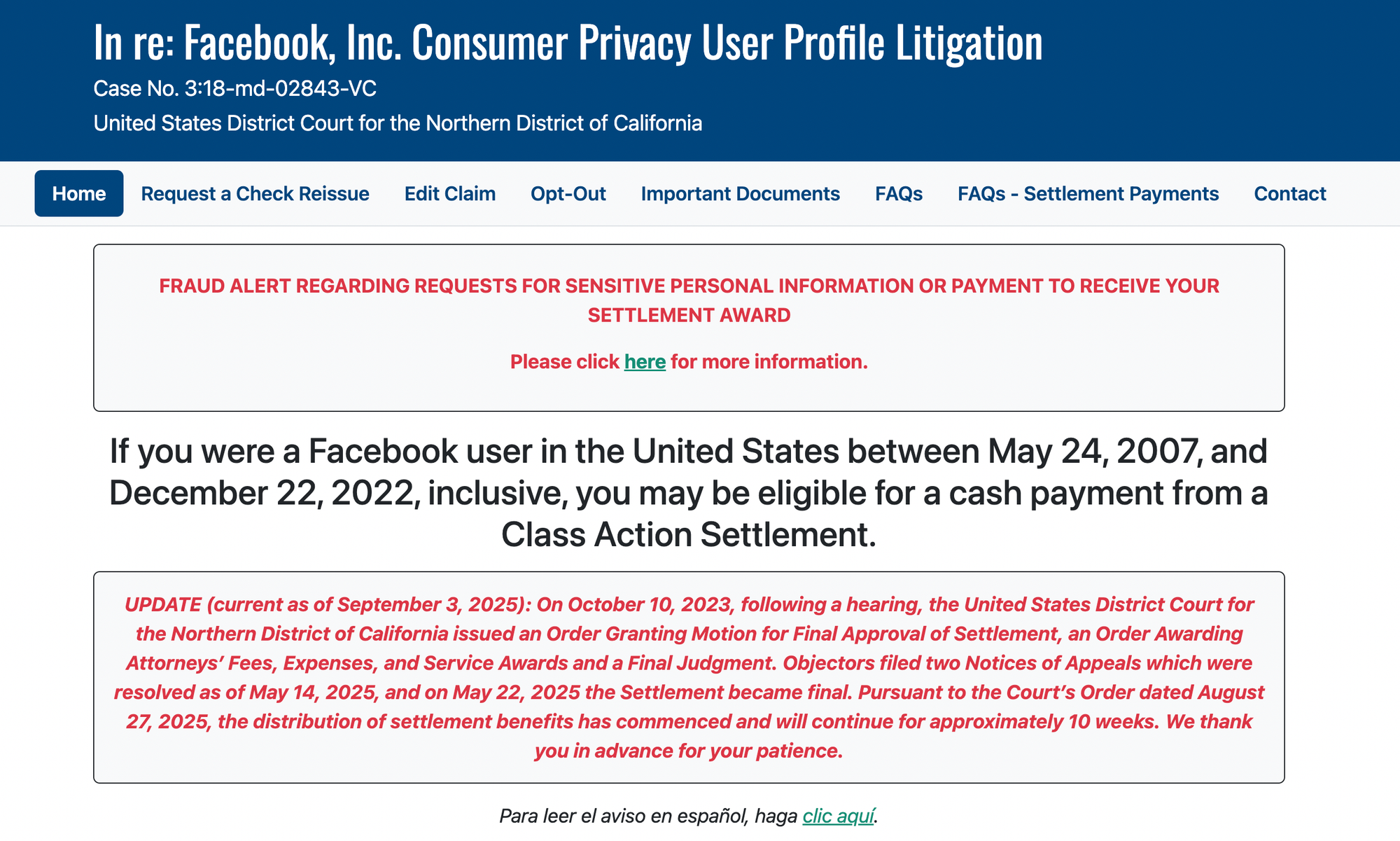

In 2025, Facebook’s parent company Meta Platforms, Inc. began disbursing payments from a $725 million settlement to millions of eligible U.S. users. The payout marked the conclusion of a multiyear legal battle over one of the most significant privacy scandals in modern history - the unauthorized harvesting and misuse of user data exposed in the 2018 Cambridge Analytica investigation.

While the scandal itself is now more than half a decade old, its legal and technical ripples continue to shape privacy law, engineering practice, and corporate accountability. This case is not merely about the disclosure of personal data; it is about systemic governance failures - the breakdown of consent, the lack of oversight over third-party access, and the structural weakness of privacy-by-design controls in social-media architectures.

The 2025 settlement stands as both restitution and warning: restitution for users whose data was mishandled, and warning to every technology company that opacity in data-sharing will eventually carry a measurable price.

2. Background: From Cambridge Analytica to Class-Action

The roots of the lawsuit trace back to Cambridge Analytica, a British political consulting firm that exploited Facebook’s developer platform to harvest the data of up to 87 million users under the guise of academic research. This data was subsequently used for psychographic profiling and targeted political advertising, triggering global outrage and investigations by regulators on both sides of the Atlantic.

Meta faced congressional hearings, record fines from the FTC, and a loss of public trust that wiped billions off its market capitalization. But perhaps most significantly, the scandal opened the door to class-action litigation in the United States, where users alleged violations of:

- The California Constitution’s right to privacy

- The Stored Communications Act and Wiretap Act

- Common-law torts for intrusion upon seclusion and breach of confidence

- State consumer-protection and unfair-competition statutes

Over years of litigation, plaintiffs’ attorneys consolidated hundreds of claims into a single federal case in the Northern District of California, which Meta ultimately agreed to settle without admitting wrongdoing.

3. The Settlement Mechanics: Eligibility, Payments, and Process

The Facebook User Privacy Settlement applied to anyone in the United States who held an active account between May 24, 2007, and December 22, 2022 - roughly fifteen years covering the full evolution of the Facebook platform.

The settlement administrator used a proportional allocation model based on months of account activity. Each month of use earned one “point.” A claimant with 120 months of account activity, for instance, received 120 points. The fund, after deducting attorneys’ fees (approximately $181 million), administrative costs, and incentive awards, was divided pro rata among all valid claimants.

By late 2025, roughly 17 million users had filed approved claims. Average individual payments ranged between $29 and $40, though amounts varied depending on account longevity and verification method.

Distribution was executed through multiple digital channels - PayPal, Venmo, ACH direct deposit, or pre-paid Mastercard - to minimize friction and ensure traceability.

While the per-user payment may seem nominal, the aggregate scale of $725 million renders it the largest privacy class-action payout in U.S. history, eclipsing even the 2020 Equifax breach settlement.

4. Technical Breakdown: Where the Privacy Controls Failed

a. Over-Permissive APIs

Between 2010 and 2015, Facebook’s Graph API v1 allowed third-party applications not only to access data from consenting users but also from those users’ friends - a design that turned a single consent into a cascading data-extraction event.

Developers could obtain profile information, likes, check-ins, and relationships for millions of users who had never interacted with the app.

b. Absence of Granular Access Controls

The platform lacked token-level restrictions and did not enforce contextual access boundaries (time-bound or purpose-specific tokens). Once an app was granted access, that access often persisted indefinitely, even if users revoked permissions or deleted their accounts.

c. Inadequate Vendor and Partner Oversight

Facebook permitted hundreds of “integration partners” - advertisers, analytics firms, and data brokers - to access sensitive data under opaque agreements.

Many partners lacked data-security certifications or independent audits. Some were overseas entities subject to different privacy regimes, complicating enforcement and data-transfer compliance.

d. Failure of Internal Auditing and Data-Flow Visibility

At the engineering level, Meta’s data-management infrastructure lacked continuous auditing of outbound data flows. Data once exfiltrated through APIs or partner pipelines was effectively untraceable; there were no unified deletion workflows or logging standards capable of proving full erasure.

5. Legal Significance: Consent, Fiduciary Duty, and Data Stewardship

The case crystallized the emerging legal concept of data fiduciary responsibility - that companies entrusted with personal data owe duties of care, loyalty, and transparency to users, akin to fiduciary duties in corporate or financial law.

Courts and regulators emphasized that “consent” must be:

- Informed: Users understand what data is collected and why.

- Specific: Each use case requires distinct authorization.

- Revocable: Users can withdraw consent as easily as they give it.

Facebook’s structure - with buried settings and implied consent through default configurations - failed all three tests.

This litigation thus re-established the principle that “opt-out by design” is not consent by law.”

Moreover, it extended liability beyond direct collection to downstream sharing.

Even if third parties misused the data, courts treated the initial data controller (Meta) as responsible for failing to vet, monitor, and constrain those parties.

6. Regulatory Context: FTC Orders and Global Alignment

Parallel to the class-action, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) pursued its own administrative enforcement, resulting in a separate $5 billion fine in 2019, the largest ever imposed for privacy violations at that time. That order required Meta to establish a comprehensive privacy program supervised by an independent assessor for 20 years.

Internationally, the scandal reinforced the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as the de facto global benchmark for accountability and user rights.

Even though the settlement occurred under U.S. law, it drew heavily on GDPR-inspired principles: data minimization, purpose limitation, and controller responsibility.

For multinational platforms, this convergence means that non-compliance in one jurisdiction increasingly exposes liability everywhere.

7. The Economics of Privacy Failure

While $725 million is less than one percent of Meta’s 2024 revenue, the true cost of the scandal lies in reputational erosion and regulatory constraint.

Following Cambridge Analytica, Meta faced shareholder lawsuits, reduced advertising trust, and a measurable decline in daily active users across key markets.

For smaller organizations, an analogous failure would be existential.

Legal defense, forensic investigation, and notification costs can surpass insurance limits, while loss of platform privileges or API access can end entire business models.

The economic takeaway is simple but sobering: privacy governance is capital preservation. In a world of increasing class-action momentum and regulator coordination, investing early in data-protection engineering is not a compliance expense but a form of risk hedging.

8. Engineering Lessons: Building Privacy into Architecture

The Facebook settlement reinforces that privacy must be engineered, not retrofitted. Security teams and developers should translate legal obligations into technical controls:

- Data Mapping and Inventory: Maintain dynamic diagrams of data flows, identifying every external sink or API endpoint.

- Access Control and Least Privilege: Apply attribute-based policies and renewable tokens; revoke unused permissions automatically.

- Data Minimization: Collect only fields essential to a transaction; anonymize or pseudonymize wherever possible.

- Retention Policies: Enforce time-bounded data lifecycles with automatic deletion jobs and verified destruction logs.

- Monitoring and Auditing: Implement continuous-audit pipelines that generate immutable records of data access for regulator inspection.

Such controls turn abstract legal duties - “limit processing,” “ensure deletion,” “maintain accountability” - into measurable, automatable system properties.

9. Broader Policy Impact: The Fragmented U.S. Privacy Landscape

The Facebook settlement accelerated legislative momentum at the state level.

By late 2025, twelve states had passed comprehensive privacy laws, including California, Colorado, Virginia, Connecticut, Utah, Texas, and Oregon, each with unique definitions and enforcement frameworks.

Without a federal baseline, corporations must navigate a patchwork of overlapping obligations: different notice formats, opt-out mechanisms, and age-verification standards. This complexity increases compliance costs but also creates incentives for a national privacy statute modeled loosely on the GDPR.

At the same time, regulators are turning their gaze toward AI and automated decision-making, where opaque algorithms amplify privacy risks.

The FTC’s recent statements suggest that privacy violations arising from model-training datasets will be treated as unfair or deceptive practices - extending this enforcement lineage into the machine-learning era.

10. Reputational Rehabilitation and Governance Reform at Meta

In response to the cumulative fallout, Meta launched a multi-year compliance overhaul. It restructured its data-governance organization, embedding Chief Privacy Officers within product divisions, integrating Privacy Review Boards into the development lifecycle, and issuing annual transparency reports audited by external assessors.

While these measures improved accountability, they also highlight a systemic truth: governance must scale with product complexity.

Platforms operating at the size of Meta process trillions of data points daily; privacy controls cannot depend on manual policy review but must be woven into the software supply chain itself.

11. Conclusion: The Legacy of the Facebook Settlement

The Meta privacy settlement is not merely the end of a scandal - it is the beginning of a jurisprudential era. It demonstrated that privacy violations once considered “ethical lapses” can now be quantified, litigated, and monetized at massive scale.

It fused technical negligence with legal liability and redefined user data as an asset governed by duties, not mere ownership.

For engineers, the case demands a shift from reactive patching to proactive architecture. For attorneys, it underscores that privacy compliance is no longer a niche specialty but a cornerstone of corporate governance.

And for the public, it proves that collective legal action can enforce digital accountability where regulation lags.

The Cambridge Analytica fallout has finally reached its fiscal conclusion - but the broader reckoning has only begun. Every company that stores, analyzes, or monetizes user data now operates under the precedent that privacy negligence is financially material, legally actionable, and reputationally irreversible.